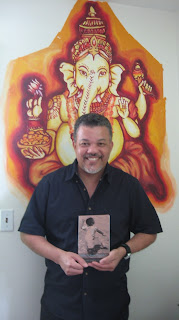

Garry Steckles is a widely traveled journalist whose career as an editor has taken him from his native England to Canada, the Caribbean, the United States and the Middle East and who has been writing about Caribbean culture since the early Seventies.

Steckles' stories, features and columns have appeared in dozens of major newspapers and magazines on both sides of the Atlantic, including the

Sunday Times of London,

Billboard,

LA Times,

Toronto Star,

Montreal Gazette,

Vancouver Province,

Caribbean Beat (the inflight magazine of Caribbean Airlines),

The Beat (the LA-based reggae and world beat magazine), the official magazine of Reggae Sunsplash,

Maco Caribbean Living,

St. Kitts and Nevis Visitor, the in-house magazines of the Sandals and Marriott hotel chains,

Chicago Sun-Times and

Jamaica Sunday Gleaner. He was founding editor of

Caribbean Week, a Barbados-based bi-weekly that covered and was circulated around the entire Caribbean. He has hosted Caribbean radio programs in Montreal and St. Kitts, and promoted many reggae concerts in Montreal.

Bob Marley: A Life, is his first book. It is published worldwide as part of the Caribbean Lives series by Macmillan Caribbean (ISBN: 9781405081436; website

www.macmillan-caribbean.com) except in North America, where it is published under licence by Interlink Publishing (ISBN 9781566567336; website

www.interlinkbooks.com)

1. Why another book about Bob Marley?

It's the question I've been asked most often since

Bob Marley: A Life was published last year, and it's perfectly valid. There have indeed been a lot of books written about Bob since he left us, at least in the physical sense, all those years ago, and many of them have been excellent.

So I usually answer that question with another question: Why not?

If the world has been ready for hundreds of books on people like Stalin, Hitler, Bush (George W, who I sincerely believe belongs in this evil company) and other world figures who have been responsible for so much human misery and destruction, surely there's nothing wrong with "another" book about a man who did nothing but make people all over the world happy - and whose message of peace and love will endure for as long as there are people on the planet (which, the way we're heading, may not be all that long ... but I digress).

The other point I always make, which I think is just as important, is that

Bob Marley: A Life is the flagship book of an ambitious series being launched by Macmillan, the giant UK publishers, on important Caribbean lives. The 20-odd names in the pipeline include the great Trinidadian cricketer and rights activist Sir Learie Constantine (already published, to critical acclaim), Marcus Garvey, Louise "Miss Lou" Bennett, Fidel Castro, Jimmy Cliff, the Mighty Sparrow, Sir Garry Sobers, Derek Walcott, Toussaint L'Ouverture, George William Gordon and Claude McKay. I can only imagine the uproar in the reggae world if Bob Marley, without a doubt THE most important, the most influential, the most famous person ever to emerge from the Caribbean, had not been included in the series.

So when James Ferguson, the Caribbean Lives series editor, called me at home in St. Kitts to tell me about the upcoming project and ask if I'd be interested in taking on the Marley book, it was an offer I simply couldn't refuse. And didn't. I certainly wasn't about to write a bio of Bob on my own initiative and hope some publisher, somewhere, would pick it up; but when one of the world's biggest publishers puts an opportunity like that the way of a journalist who's spent more than three decades writing about Caribbean music, there really isn't much you can say except "I'd love to. How many words do you want and when do you need the manuscript?"

2. Why did Macmillan choose you to tackle the Marley book?

The simple answer is that James Ferguson, among many other things, is also the literary editor of

Caribbean Beat, the excellent in-flight magazine of Caribbean Airlines (formerly BWIA International). I've been writing about music and culture for the magazine since the mid-to-late Nineties, and, inevitably, Bob has featured regularly in my Riddem'n'Rhyme column .... sometimes to the point where the magazine's editors have had to beg me not to mention him for a few issues. James had read my column, liked it, and my commission from Macmillan stemmed from that.

And I'd like to think I was pretty well qualified to take on the project. I've been writing about Caribbean music since the early Seventies, mainly in big-city newspapers in North America and magazines in the Caribbean, and have also been heavily involved as a concert promoter (including shows by Peter Tosh, Toots and the Maytals, Ken Boothe, Leroy Sibbles, Carlene Davis and Ernie Smith). I've hosted Caribbean radio programs on mainstream radio in Montreal and St. Kitts, and, over the decades, I've seen just about every roots reggae great perform and met and/or interviewed almost all of them. I've played soccer with Burning Spear (at his Marcus Garvey Youth Club in St. Anne, where Spear and a bunch of teenagers ran me off my feet), burned one down at Jimmy Cliff's house in New Kingston, downed a few cold ones with the late Alton Ellis at a show in Montreal, where we happily chatted about rock steady and the delights of English pubs, accompanied Ras Michael and the late Jacob Miller to an incredible concert for the prisoners in Spanish Town Jail, hung out backstage with the late Joseph Hill, toured with and cooked for Peter Tosh, Sly, Robbie and the rest of the Word, Sound and Power band, drove Carlene Davis to the Ranny Williams Centre in Kingston the year she became the first female performer to get a solo spot on a Reggae Sunsplash lineup (that was 1980, the year of the 'missing' Sunsplash; I've read in several places it didn't happen, because of the pre-election violence gripping Kingston - trust me it did), hung out with Tommy Cowan and the guys at his Talent Corp yard around the corner from the Pegasus in Kingston in the days when IC Oxford Road was THE hangout of choice for the roots reggae young lions of the Seventies, hung out with Bob & Co at 56 Hope Road in the week leading up to the Peace Concert in 1978, fired back a few with Sparrow, Duke, Crazy and other calypso greats backstage at shows in Montreal, felt my heart moving in my chest in time with the bass pounding out of the gigantic speakers at sessions in the late Jack Ruby's yard in Ocho Rios, and spent way more time than I should have at innumerable JA shows in smoky community halls and church basements in Montreal and Toronto.

3. Did you have any initial doubts about writing a biography about Bob?

I felt quite comfortable tackling the Marley book. But I also knew it would be a huge challenge. How, I wondered, could I bring something new to the table? I wasn't about to discover a Marley tour no one had heard about. Or a "missing" album. Or, come to think of it, any event of massive significance that previous biographers might somehow have overlooked. So, perhaps inspired by Bob himself, I decided the best thing to do was keep it simple, and try to write a book that accurately covered the most important and significant events of Bob's short but remarkable life and also full of anecdotes that would appeal both to Marley vets and also to people who may have discovered his music comparatively recently and might be interested in knowing more about him.

Equally important, I wanted to use Bob as an example of how it's possible to become rich and famous without losing sight of your roots. One of the things - one of the many things - that I have always admired Bob for was the fact that he didn't change, and that one of the first things he did when he started to make serious money was to give it away - much of it to poor people from Kingston's ghetto areas, who used to line up at 56 Hope Road and tell Bob what they needed money for. And, almost inevitably, they'd get what they needed. There was no fancy mansion, no bling, none of the grotesque excesses that modern generations of so-called superstars have inflicted on their fans.

The other major decision I made was to keep myself out of the narrative. Much of what I write about happened when I was at the scene, and I have to confess it was tempting to start writing "I" this and "I" that. I even started the book with a chapter in which I crept into the story ... and then realized, with more than a little help from my wife Wendy, whose encouragement and support made the whole project doable, that readers really don't care a hoot about me - and why should they, they want to read about Bob Marley? Any lingering doubts I might have had about the wisdom of that decision disappeared when I checked out another book about Bob, one that was published while I was about half-way through writing my own.

For obvious reasons, I'd rather not be specific about the title of the book or its author; suffice it to say that the first paragraph (a long paragraph, admittedly) contained the word "I" 16 or 18 times. I discovered that the author had been born in Jamaica but moved to the US as a youngster and couldn't speak with a Jamaican accent. I was told how he was so well-connected he'd managed to land a rare interview with Bob's mother, Cedella. I learned that he'd actually been to Trench Town, and that he clearly considered himself a pretty cool sort of guy .... and I found out zilch about Nesta Robert Marley. I couldn't stomach too much more, but it was a valuable lesson, and I managed to write my bio without a single "I". I'm perhaps inordinately proud that I described perhaps Bob's most famous stage appearance, at the One Love Concert for Peace at Jamaica's National Stadium in April of 1978, without mentioning that not only had I been there, but that I'd seen the show from the first notes to the last from perhaps the best seats in the house, front row, centre, with the then Jamaican PM Michael Manley and his entourage sitting in the row behind me.

4. Were there any personalities in particular that stood out in the writing of the book?

The book also gave me an opportunity to write about one of the most remarkable people I've ever met, the New York-based Liverpool-raised PR genius Charles Comer, whose huge contributions to Bob Marley's success story have seldom, if ever, been fully documented or appreciated. I first crossed paths with Charles when I was writing reggae stories for the Toronto Star in the mid-Seventies. I would often call Island Records in New York for background info, and I was always put through to Charles, who had been hired by Island to deal exclusively with Bob. Inevitably, we realized right away we were both from the north of England - Charles from the western port city of Liverpool, myself from the north-eastern ship-building and coal-mining town of Newcastle-upon-Tyne ... of carrying coals to Newcastle fame. We became friendly over the phone, and finally met in person in Jamaica, when Charles was working feverishly to convince journalists that the Peace Concert was really a Bob Marley spectacle, with a few other reggae performers thrown in to keep the crowd interested until star time. Bob, I suspect, would have been horrified. Within a few years, Charles was to become one of my dearest friends, and, over the years, I had virtually unlimited access to his clients - among them Bob, Peter Tosh, and also mainstream blues and rock musician like Stevie Ray Vaughan and the legendary Irish group The Chieftains.

5. What else can you tell me about Charles Comer?

He was, in just about every way, a unique character. On the surface, he was about as unlikely a publicist as you could imagine for Rasta musicians. He was wise enough not to make the slightest attempt to meet them on their turf - and he made it clear, from the moment he took them on as clients, that they'd do things his way or it was no deal. Even Peter Tosh, a proud man who took no nonsense from anyone, was intimidated by him.

I vividly recall one incident, backstage between two shows at a big nightspot in Boston, when a reporter approached Peter and asked if he could spare him a few minutes. "You'll have to speak to Charlie Comer first," replied Peter. "I don't talk to any press without his okay." A year or so later, I was on the road with Peter and the band in Canada, and Charles had organized an early-morning interview for Tosh with the CBC. I was given the job of driving the two of them to the CBC studios in Toronto, and we had to be there at the unearthly hour - for a musician - of 9:30 in the morning. We knocked on Peter's hotel room door around nine, and it was opened by a half-dressed, half-awake Tosh with the first (at least I think it was the first) spliff of the day in his hand and barely lit. Charles was furious. "Put that spliff out, Peter Tosh," he commanded. "And get yourself dressed. We have to be at the CBC in less than half an hour." I waited for Peter to explode. He didn't. "Yes Charlie, I'll be right with you," he said, putting out the spliff - after a couple of semi-defiant tokes - and jumping into his clothes in double time.

The thing with Charles of course, was that, like Bob before him, Peter knew that his career had taken off since Comer became his main PR man. And he knew it wasn't a coincidence. Charles, who had also worked with the Rolling Stones for many years, was instrumental in arranging Mick Jagger's surprise appearance with Peter on

Saturday Night Live in December of 1978, where they sang, "You've Gotta Walk and Don't Look Back," the duet they'd recorded and which became the biggest single of Peter's career.

As for Peter himself, I have to say that despite his reputation for having a short fuse I always found him perfectly easy to get along with. This has been the case with just about every reggae performer I’ve encountered since I started to get closely involved with the music all those years ago. I feel privileged to have been welcomed into their world, and, through my efforts in writing about it, to have been able to contribute in a small way to spreading reggae's message.

***

I became a member of PEN because of their unwavering support of writers and our freedom of speech. For members, this is not merely an idyllic concept. PEN members demonstrated this when they coordinated the release of a young poet, Orlando Wong, from jail. Wong would later change his name to Oku Onoura and the literary history of Jamaica would be changed because along with Mutabaruka, Mikey Smith, Malachi Smith, and Oku, the birth of dub poetry on this side of the Atlantic was given a chance to survive.

I became a member of PEN because of their unwavering support of writers and our freedom of speech. For members, this is not merely an idyllic concept. PEN members demonstrated this when they coordinated the release of a young poet, Orlando Wong, from jail. Wong would later change his name to Oku Onoura and the literary history of Jamaica would be changed because along with Mutabaruka, Mikey Smith, Malachi Smith, and Oku, the birth of dub poetry on this side of the Atlantic was given a chance to survive.