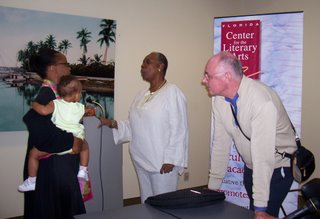

“You are not born a Caribbean writer—you become a Caribbean writer.” With that opening statement, Maryse Conde, author of twelve novels—including I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem; Windward Heights; Crossing the Mangrove, and Desirada, began her reading on Thursday, April 6, 2006 at the Historical Museum of Southern Florida.

“You are not born a Caribbean writer—you become a Caribbean writer.” With that opening statement, Maryse Conde, author of twelve novels—including I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem; Windward Heights; Crossing the Mangrove, and Desirada, began her reading on Thursday, April 6, 2006 at the Historical Museum of Southern Florida.A spellbinding storyteller with an expansive knowledge of philosophy and aesthetics, Conde described her journey from Guadeloupe, “We are the last of the colonialists,” to Paris, France where she discovered her vocation. As she explained, “I always thought that to be a writer, you had to white and dead.” While in Paris, she began to ask one of the questions that occupies her creative life: What does it mean to be a Caribbean writer?

Her answer took her from France to Guinea. For as she learned about the complexities of the subject, she also re-discovered her African ancestry: “Slavery did not exist in my family. It was something of which we were to be ashamed.” Her readings of Frantz Fanon’s, Black Skins, White Masks, led her to Guinea where after twelve years she concluded, “I had no place in Africa.” It was primarily the differences in food, music, language, and religion, “Religion gives you a means of relating to yourself and other people,” that she realized how much she had idealized Guinea/Africa, so she decided to return to Guadeloupe.

This is not to say that her transition to Guadeloupe with the other Negropolitans was easy, for she was always asked the question: Are you on the Kreyol side or the French side? The frequency of the inquiry led her to speculate about language and identity from which she deduced that while language, Kreyol, is an important marker, it is not the only marker that distinguishes one as Caribbean. With that understanding, she began to experiment with the images, sounds, and characters that were uniquely Caribbean while disconnecting herself from the more insular demands from her colleagues, “Writing is the only sign of freedom—you have no master.” Again, the idea of freedom came back to haunt her as she realized that many the Caribbean intellectuals did not share her ideas about developing a narrative strategy that was different from the European ideal. Nor did they share her ideas about race, gender, and economics and their link to economic and psychological dependence.

It wasn’t until she came to the US, however, that she fully confronted the issue: What does it mean to be black woman born in the Caribbean? The question literally fell into her hands when a short biography of Tituba landed in her palms as she was walking through a library. She saw many similarities between Tituba’s and her own experiences that involved issues of race and gender, yet as she explained, “It was important for me to know myself.” That quest to know herself has taken her on a grand adventure and has yielded many important insights: “When a writer can say, ‘Here is my voice,” it is an accomplishment.”

First published on April 10, 2006