GP: Malachi, it's been 14 years since I last interviewed you How has your work changed since that interview?

Malachi: A lot has changed in my life and career since 2006. I would like to think that I am now a more mature writer and student of life. I'm no longer shackled by the constructs of a 9 to 5 in a system that always forced me to stand firm and uphold my principles. I am my own man. I don't need to beg, bow, or borrow. I am totally liberated.

I have also grown in my writing. My pen is deliberate and concise. Traveling the world and experiencing different cultures has also contributed enormously to my world view and growth. I am also writing more prolifically. I have written some short stories, finished one work on the turbulent era in Jamaica, Blood Fi Blood, Fire Fi Fire: I Was There Too, almost completed another piece on my journey in the Jamaica Constabulary Force, and I’m working on other projects.

The launch of my annual Jamaican Poets Schools Nomadic Tour has been great. Taking poetry into schools and communities and see students, young poets, and academics come alive in real-time.

Finally, I’m hosting a radio show, Strictly Roots dub poetry, and more on WZOP 92.7 and WZPP 96.1 FM. It has always been a dream of mine to take poetry to the people via the airways. It is working magic. Other radio personalities are now playing poetry as part of the shows.

GP: On the title track, "Ticked Off," you've expanded the meaning of "I Can't Breathe." Why do you think George Floyd's death has sparked such a worldwide outrage?

Malachi: What the world witnessed was brutal, horrific, and downright disgusting. It is like the officer was saying, "I got this; stand back, this neck is mine."

It was my neck. It was my people's neck. For 400 hundred years, we have been saying that this is happening, but the truth was always covered up while we suffered and bled and died. In a world with so many intuitions of justice and Christianity, it's perfectly normal to lynch a black man because we are always wrong.

GP: In a collection with so many hard-hitting poems about social justice, I was surprised by the inclusion of "Blacker de Berry." Why did you include this poem in this collection?

Malachi: I'm proud of how my beautiful black mothers and sisters, queens, and empresses, have come into their own. So, this ties into the contemporary narrative. I love to uplift and elevate them, hence the inclusion. I took into consideration too that the original recording could have technically been better. Hopeton Lindo told me recently that it was his favorite poem, and then Taurus Alphonso said I should redo it and change the arrangements.

GP: I've also noticed that you have branched out to tackle the theme of mental health on the track, "In my Head." Why did you think it was necessary to deal with this issue?

Malachi: The song, “Say My Name” by Novel-t kept calling me. I met a young man, Haile Clacken, some years ago at the Talking Tree Poetry Festival in Treasure Beach, Jamaica. I started a conversation with a librarian, and this young man walked over. She introduced him to me, and we had a nice conversation. He told me he liked my poems. Less than a year later, the librarian sent me a message on What's App with the photo of Haile and asked me if I remembered him. I replied, yes, of course. She responded he was shot and killed.

Well, actually, he was murdered. Haile, a trained teacher, attended college overseas, suffered from mental illness. On the day he was murdered, he set out on foot to visit his only child and suffered a mental lapse along the way.

Haile climbed on top of an armored car, and they drove off with him on top. The driver tried to dislodge him by driving aggressively. To avoid falling off Haile clung to the vehicle's wiper. When the vehicle stopped, Haile climbed down. There was no struggle with the guard. He just blasted him. Many people witnessed the crime. The guard was charged for murder, and in typical Jamaican justice fashion, four years later, the case still hasn’t been tried.

My good friend, Jean Binta Breeze, also suffers from mental illness and has written about it in her poetry. It is a real issue that needs our collective attention. There is also a new branch of study/philosophy that deals with the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade post-traumatic syndrome. The way we kill each other too on our streets is a manifestation of this mental illness.

GP: Bob Dylan seems to be an unlikely candidate for your homage in "Beat Down Zion's Door." Why did you choose that song by Bob Dylan?

Malachi: I have always been fascinated by this song, but instead of just “knocking,” I am convinced that we need to beat down some constructs that are tied to and justified by religion(s). Many have become prisoners to holy books, and in the process, truths, rights, and justice are trampled.

Dylan is polite. I am tired, frustrated, angry, uncompromising. I am demanding answers. I want them now. I have no use for propaganda. The way the UN and other organizations that are here to protect the earth's sufferers have manipulated facts, leaves a lot to be desired. So, I want to have a chat with the Father and seek out his reasoning, so I barged in.

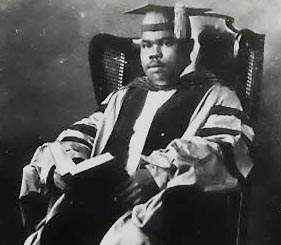

About Malachi

Malachi Smith is an accomplished Jamaican writer of poetry and plays, and an actor, performing in his own plays and other productions in live theatre and on radio and television. He is a fellow of the University of Miami’s Michener Caribbean Writer’s Institute where he studied poetry under Lorna Goodison and play writing under Fred D’Aguilar.

He was one of the readers at the first Talking Trees in May 2011, and appeared again at the second Talking Trees in 2012, and returns to the Talking Trees stage on May 27, 2017. Malachi's earlier appearances include being the headliner in 2004 at the International Dub-Poetry Festival in Toronto and in 2008 at the Love-In Festival in Miami with Richie Heavens and other greats. He also made three appearances in New York, and toured St. Kitts and Nevis in the summer of 2000 to rave reviews. More recent appearances include: 2012 - International Poetry Festival of Colombia, Medellin, Colombia; 2014 – International Poetry Festival of Nicaragua; 2015 – International Poetry Festival of Taiwan; 2016 – Poetry Africa, Durban, South Africa; 2017 – Polokwane Literary Fair, Limpopo, South Africa - Hon. Louise Bennett-Coverley Reading Festival, Broward Community College; and 501 Café, New York. 2018 – Honduras International Poetry Festival, University of the West Indies, Bookophilia and other locations in Jamaica; 2019 – Festival Contemporanea San Cristobal, Mexico, La Guagua Poetry Festival, Lowell, Massachusetts; 2020 – Toured Jamaica with Judith Falloon-Reid’s, An Awe Inspiring Journey – Down in Antarctica (featured on the team song with Falloon-Reid).

His awards include the 2016 Akamedia Award in the Reggae Category for his poem How Yuh Mek Har and the Jamaica Cultural Development Commission’s (JCDC) 4th Place Choice Writer (gold and bronze medals) 2018; Best Adult Poet in 2017 and 2014, following earlier JCDC awards: 2009 most outstanding writer in the poetry and 2006 four Literary Awards for poetry and playwriting. Also, in 2006 he won the Joe Higgs Music Award for dub poet of the year, and was nominated for the dub poet of the year in the Reggaesoca Awards, and for the poet of the year in the Martin’s International Music Awards. He has been a nominee in the IRAWMA Award for Best Poet (2012 -2016). Malachi was one of the 50 Jamaicans living in the USA, who were special honored for their contribution to Jamaica on Jamaica’s 50 year of independence.

Launched Jamaican Poets School Nomadic Poetry Tour in 2017. Coordinates the annual, Louise Bennett-Coverley Writer’s Clinic. Featured on the 2020 Yasus Afari produced album, Dub Poetry Ina Yu Face.

The documentary film, Dub Poetry: the life and work of Malachi Smith premiered in 2007.

Malachi’s CDs include Hail to Jamaica, released in 2011; Scream, released in 2014; and his latest 2017 release, Wiseman. He is awaiting publication of two new poetry collections, The Gathering and Stony Gut, and is currently writing a series of short stories.

An alumnus of Florida International University (M.S.C.J. & B.Sc.), Miami-Dade College (AA) and Jamaica School of Drama, Malachi was one of the founding members of Poets in Unity, a critically acclaimed ensemble that brought dub-poetry to the forefront of reggae music in the late 1970s, and carried it forward for a decade.

In addition to being a poet, Malachi served in the police force in Jamaica and in Florida, retiring from the latter in 2016. He was a freelance writer for the Jamaica Daily Gleaner (Overseas Edition), a board member of the Jamaica Ex-police Association of South Florida, as well as the Caribbean Education Foundation; and the Honorable Louise Bennett-Coverley Heritage Council. Malachi is married to his childhood sweetheart Marcia and has two sons Maurice and Marlon.