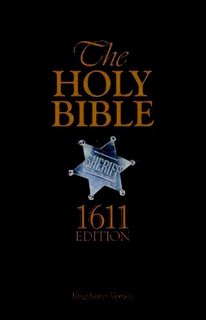

Westerns and the King James Version are two of the main staples of the Jamaican imagination. This is understandable because both share a similar plot and a cast of recognizable characters. The King James Version and most Westerns begin with trouble (original sin or “bad guys” in Dodge City), a “good guy” or hero emerges in the middle of the feud (Samson or Wyatt Earp), and an alignment of forces leads to a final showdown (OK Corral or Valley of Megiddo). The bad guys (Satan or the Clantons) are annihilated; the good guys win and ride off into the sunset on their white horses.

Westerns and the King James Version are two of the main staples of the Jamaican imagination. This is understandable because both share a similar plot and a cast of recognizable characters. The King James Version and most Westerns begin with trouble (original sin or “bad guys” in Dodge City), a “good guy” or hero emerges in the middle of the feud (Samson or Wyatt Earp), and an alignment of forces leads to a final showdown (OK Corral or Valley of Megiddo). The bad guys (Satan or the Clantons) are annihilated; the good guys win and ride off into the sunset on their white horses.

The fictions that have emerged from Jamaica also follow a similar pattern. But given the history of colonialism and racism in Jamaica, the stories sometimes parody the conventions. For example, in the classic Jamaican film, The Harder They Come, there are clearly discernible “bad guys” (record producers) and a “good guy,” Ivan, a singer who is willing to make any sacrifice for his music. Because of the unfair treatment by the record producers, Ivan’s crimes begin small, but then escalate when he takes the law into his own hands. This leads to a showdown on a North Coast beach. To a certain extent, the actions that lead up to Ivan’s shootout with the police are inevitable because Ivan was thrust into an unjust system and given his temperament, the resulting bloodbath was to be expected. Yet, what is made clear in the film is that Ivan’s original sin was being born Black.

“I was born with a price on my head,” said Bob Marley in a 1978 interview (Bob Marley in His Own Words by Ian McCann). It is interesting to note that Marley uses the language of the “Wanted” poster to describe an almost fatalistic viewpoint which seems uncharacteristic with his usual positive viewpoints and the teachings of Rastafari. Yet, both these themes are also evident in one of this most popular song, "I Shot the Sheriff.”

The song begins with the speaker already in trouble, “All around in my home town/ They are trying to track me down/ They say they want to bring me in guilty/ For the killing of a deputy/ For the life of a deputy.” The speaker knows the system is stacked against him because he is to be brought in “guilty” for a crime he would never deign to consider, “the killing of a deputy.” Deputies are not in his league. He knows he killed the “Sheriff” and it is a “capital offense.” But he has an explanation.

“Sheriff John Brown always hated me/ For what I don't know/Ev'ry time I plant a seed/ He said, "Kill it before it grows."/ He said, "Kill them before they grow." The anonymity of “Sheriff John Brown” makes it clear that the “Sheriff’s” influence is pervasive (almost like Agent Smith in The Matrix), and the speaker’s plight has been brought about not by anything that he has done, but by the enmity that “Sheriff John Brown” has towards him for a Kafkaesque crime for which the speaker knows there is only one possible ending: death. The "seed" is metaphorical and could stand for any on the "dangerous" ideas that Rastafari espouse: humans as god or each human as ultimately responsible for his/her choices. These ideas would be a threat to any sytem of dominance and control represented in the Bible as Pharoah, Herod, or Nebuchadnezzar or in the speech of Rastafari as Rome or Babylon and would have to be "killed" or stopped before they could spread among the populace who would embrace these ideas of freedom. Something has to give.

The key to understanding the lyric comes in the final stanza: “Freedom came my way one day/ And I started out of town/ All of a sudden I saw Sheriff John Brown/ Aiming to shoot me down/ So I shot, I shot, I shot him down/ And I say, if I am guilty I will pay.” This was not a fight that the speaker wanted, but the situation was created by the “Sheriff.” The speaker was willing to leave, but the “Sheriff” was about to kill him, so he acted in self-defense. The speaker concludes his ballad with a complex blend of Rastafari and Jamaican mythology and folklore.

"The Sheriff," then represents the antithesis of freedom--the repressive codes of conduct that have been codified into laws that serve the oppressors and have been internalized as the "proper" codes of conduct. In Western mythology, it's the dragon that must be slain.

"The Sheriff," then represents the antithesis of freedom--the repressive codes of conduct that have been codified into laws that serve the oppressors and have been internalized as the "proper" codes of conduct. In Western mythology, it's the dragon that must be slain.

“Reflexes had the better of me/And what is to be must be/Ev'ry day the bucket a-go-a well/One day the bottom a-go drop out.” The speaker’s defense rests on his claim: “Reflexes had the better of me.” It is to be noted that within Rastafarian mythology, for the Nya man of Africa, the natural, original man who lives in complete harmony with life and his surroundings, “reflexes” are not a crime (Rastafari: An Ancient Tradition). Reflexes are part of his natural makeup and his right to self-hood is expressed in the concept of InI—the mystical union of man with the divine. The Rastaman’s lifelong mission is to reflect the African Nya man in his choice of right foods and right actions (Iwa in the Yoruba religion). In Bob’s vocabulary, Nya man could also be substituted for “higher man” (“We are the children of the higher man”)—the idea of the indwelling god (the i-nity of InI) which is part of the West African religious continuum.

The speaker then says, “What is to be, must be,” and then counters with “Every day the bucket a go a well/ One day the bottom a go drop out.” Besides being another example of Marley’s lyrical balancing that is a trademark of his writing, “How long shall they kill our prophets/ While we stand aside and look/ Some say it's just a part of it/ We've got to fulfill the book,” he completes the circle with the folk wisdom of Jamaica, “Ev'ry day the bucket a-go-a well/One day the bottom a-go drop out,” and admits a kind of fatalism. However, it is a kind of fatalism that is driven by the actions of the persona. In other words, actions (desires) drive destinies. There are consequences to actions and any repeated action, “Ev'ry day the bucket a-go-a well,” is sure to bring about a certain consequence, “One day the bottom a-go drop out.” Is the hero’s destiny inevitable? We’re back to The Matrix: “Ohh, what's really going to bake your noodle later on is, would you still have broken it if I hadn't said anything?”

The song ends with the speaker’s insistence that he shot the “Sheriff” and not the deputy. This disdain for deputies is typical of heroes who even when their life is on the line recognize the greater enemy, “Go and tell that fox, 'Behold, I cast out demons’,” or “If my kingdom were of this world, then would my servants fight.” Underlings such as Herod and Pilate were the lapdogs of Rome. The real fight wasn’t with the “deputies”; it was with the “Sherriff” (or the Architect 0f The Matrix Revolutions)

In the framework of Rastafari mythology, politicians, the police and courts are lackeys of Babylon—the system of institutionalized racism/colonialism that values capital over labor. The “Sheriff,” then, would be the all encompassing externalized rules (in time, internalized which is where the real battle is fought) of Babylonian conformity--everything that if a Rastaman (Nya Man) is to be free, he must meet head-on and deny. The Rastaman asserts his dignity and right to live on moral grounds in a system that would deny his existence. The final showdown in the Valley of Megiddo or the town of Gibbeah is inevitable.

The actions of the protagonist also match the themes within Marley’s other work because the protagonist is willing to fight against an enemy that threatens his physical or moral integrity “Brother you're right, you're right/ You're right, you're right, you're so right/We gonna fight, we'll have to fight/ We gonna fight, fight for our rights” (“Zimbabwe”). The speaker is not cowering in the shadow of the “Sheriff” nor is he willing to become a martyr, “But if you know what life is worth/You would look for yours on earth/And now you see the light/ You stand up for your rights” (“Get up, Stand up’) and confronts the “Sheriff” because his life is on the line, ‘You want come cold I up/ But you can't come cold I up” (“Trench Town Rock”). He is willing to be branded as a criminal because he relies on the law of action and consequence, “For every little action/There’s a reaction,” (“Satisfy My Soul”). Or as Bob said in an interview with Neville Willoughby, “The only law is the law of life.” (So Much Things to Say)

In the symbolic language of Jamaica, an island beset on all sides by powerful forces, the identification with the “Children of Israel” has become part of the symbolic language of the nation (“The Israelites” by Desmond Dekker). Similarly, in the fictive imagination of Rastafari, the “Sheriff” is the equivalent of Babylon of which Pharaoh, Nebuchadnezzar, Herod, Pilate, Tony Blair and George Bush are “deputies.” For the Rastaman to survive, there can only be one outcome in the victory of “good over evil’ (‘War”). The hero must “shoot the Sheriff.”

***

If you are

searching for posts about Bob Marley,

Marcus

Garvey, Rastafari,

or Dennis

Scott, please check the archives.

Also, if you enjoyed this article, please visit my Author page @ Amazon.com

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=611d0ffd-fd17-48e5-96c4-20932db6f32d)

20 comments:

"That message a kind of diplomatic statement. You have to kinda suss things out. "I shot the sheriff" is like I shot wickedness. That's not really a sheriff, it's the element of wickedness. The elements of that song is people been judging you and you can't stand it no more and you explode, you just explode (Bob Marley july 1975)

do you know that Bob composed "I shot the sheriff" after watching the movie "THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE UGLY" at a cinema in Kingston?

Bwoy, dah one ya deep! I see what you are saying still, but it deep. Now I know that you really teach literature, this sounds just like a few of my lecturers when I was at UWI.

dear Mr. Philp,

I have some questions to you:

how much have you written yet about Bob? has it been published somewhere, and can it be bought somewhere? I would really enjoy your texts about Bob in book format...!

I didn't know that Bob composed I shot the sheriff" after watching the movie "THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE UGLY" at a cinema in Kingston" And I'm not surprized. Many of the things that I see in Bob's work, I also see in mine and in the work of my peers. We're all drwaing from the same well, and many i our audience share the same sensibilties.

Bob used his enormous talents in a readily accessible medium and he helped shape the imagination of writers such as Colin Channer, Kwame Dawes and myself.

Dear SNW,

If you do a Google search, you will see that I have done quite a bit of writing on Bob and reggae.

As far as the book thing is concerned, I've sorta stopped thinking about books and I just write. I made fun of the "book business" in a post, "Negril or New York," but that's just me making joke of serious things.

The bottom line on books is that they must sell, and so far it had been pretty meager.

Blogging has kept me fresh so I really don't have to worry about who will buy or sell. And I write as the Spirit moves me. So, check in every now and then for new pieces because reggae, Wailers, and Caribbean literature and a big part of my conciosusness.

Mad Bull,

Give thanks. Sometimes I really miss the classroom when I was able to do more things like this with students and together we could explore a text.

Marco,

Bob was working with metaphors(Sheriff) and so clearly the ideas of wickedness (Babylon) and judgmant (Bible) come through clearly in "I Shot the Sheriff."

bob used some simple metaphors or some simple sayings so that all the people might understand the meaning of his message

this is his greatest merit: he spoke to poor people, to uneducated people

in my opinion Marley is one of the most important educator (teacher) of the XX century

Marco, this is why I love Bob's music so much.

I mean, "Cuz puss and dog they live together, what's wrong with loving one another?" and "it's a foolish dog bark at a flying bird." Simple metaphors of agreat teacher--"light like a feather, heavy as lead."

1 Love,

Geoffrey

"Cuz puss and dog they live together, what's wrong with loving one another?"

I think that israel and lebanon must learn this

Dear Marco,

Yes, yes, yes.

1 Heart,

Geoffrey

I was ruminating this question while I was at work today. Bob Marley was a very sentient and intelligent man with powerful lyrics and an even more powerful message regarding social injustice, colonialism...etc.

Why Name the Sheriff, John Brown,the same name as one of the most vocal US abolitionists of the 19th century?

I would love to hear your thoughts.

Paul B.

Dear Paul B.

Thanks for stopping by. Paul, I don't think that Bob was thinking about that John Brown, but I may be wrong.

"John Brown" may just be a shorthand the kind of anonymous demiurge that he must overcome--Babylon.

The "deputy" is a human agent--like the police.

I hope this helps.

Bless up,

Geoffrey

Hi Geoffrey.

Brilliant page. I saw a random Wikipedia article about Sophie Blanchard - Parisienne aeronaut whose balloon crashed causing her death at the time of Napoleon. Charles Dickens responded with a quote to the effect that if you put the bucket in the well enough times - that eventually it will crack. Perhaps this is a popular analogy; but I had never heard it save for Bob Marley, 'every day the bucket a go a well...' I wonder if Bob Marley was literally citing an historical event?

Timothy Wiebe

Dear Timothy Wiebe,

Greetings and Welcome!

"every day the bucket a go a well..." is a well known Jamaican proverb that carries the folk wisdom of the people. In fact, there is a video of how he came up with the line. In the video Esther Anderson, who was dating Bob at the time, claims she helped him to remember the proverb. Whether this is true or not is another story. It does seem plausible though.

Peace,

Geoffrey

I love the link system you've developed for your posts, Geoffrey. It really helps the reader to see what new writings you have and then discover hidden gems like this one that you've already written. Hope you've "gotten together and feel alright" with friends to celebrate Bob's birthday.

Thanks, Jeff.

I've been learning along the way.

How's the traveling?

1Heart,

Geoffrey

The bucket proverb is basically saying how much can a man take before he explodes, simply put someone uses a bucket everyday to carry water from the well, eventually the bucket will fail to carry water. Shooting the sheriff put an end to being 'used'(like the bucket. Sheriff John Brown is a white officer in colonial times, he was shot by a freed slave in self defense.. another important line that ppl over look is when he says sheriff Brown alwys hated me and I don't know why. Its clear he has respect for this man and cannot understand the racial hatred white men had/has for the africans

True words, Anonymous. "Sheriff John Brown always hated me/for what, I don't know." is a powerful line that is often overlooked.

Give thanks for the observation.

One Love,

Geoffrey

Post a Comment