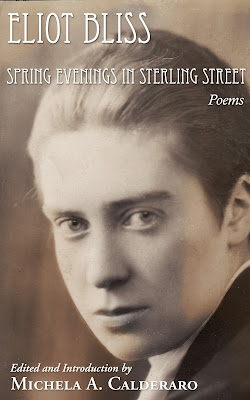

Neglected authors

fascinate me. While the particulars for their disregard may vary over time and

from culture to culture, one thing remains constant: their perseverance despite

official recognition. Such is the case of Eliot Bliss, a “white, Creole, and

lesbian” Jamaican novelist and poet whose collected poems have been resurrected

by Michela A. Calderaro in Spring

Evenings in Sterling Street.

In the

introduction to the collection, Calderaro pays tribute to Patricia Allan-Burns,

Bliss’s “faithful companion for about 60 years,” and places Bliss within the

context of Caribbean herstory: “The story of Eliot Bliss is the story of a

mermaid, as Creole women from the Caribbean often envision themselves. Indeed

they are mermaids – half something, half something else.” Calderaro also

provides a brief biography, which traces Bliss’s troubled life from her birth

in Jamaica to England where she died.

We’ll

try to follow Eileen Bliss in her journey to become herself, to witness her struggle to cast off the white British

colonizer’s daughter persona and take on that of the Creole expatriate, not

feeling comfortable in either. We’ll see her transformation from the perfectly educated daughter of a British

army officer to the acclaimed new voice of 1930s London applauded by the elite

literary circles and the scandal of

lesser-known lesbian clubs in that city. And, finally, witness how in her later

years she found herself exiled and forgotten.

Eliot Bliss was

the author of two novels, Saraband

and Luminous Isle and “very few poems

in various journals in the 1920s.” Her poems, however, were never published in

a single volume and Calderaro provides the details of her discovery:

The

poems in this collection were found in 2004 in the little apartment where Eliot

Bliss spent the last years of her life. There were two almost ready collections,

Selection of Poems: 1922-1931 and The Wild Heart: Poems 1922-1929, and

then a considerable number of loose poems – originals and edited versions – in

various places around the house, piled on dusty shelves, inside drawers, inside

old cocktail-bags, some folded in books, others in envelopes. These uncollected

poems are grouped under “Miscellaneous Poems” in this book.

Many of the poems

in Spring Evenings in Sterling Street

display Bliss’s “rich and sophisticated” language. And while poems such as “The

Green Tree,” “If I Write With My Blood,” and “The Chameleon” from Selection of Poems: 1922-1931 and “Rain

During the Night” and “The Departing Amorists” from The Wild Heart: Poems 1922-1929 demonstrate Bliss’s commitment to

her craft and mastery of a carefully wrought line, it is the poems in the

“Miscellaneous Poems”--the poems that she chose not to reveal to the world--that

interest me.

In “Transubstantiation”

and “Introibo ad Altare Dei,”

Calderaro points out that despite their seemingly pious titles, the poems “subvert

religious evocations and transform them into sexual allusions.” I will not

attempt to paraphrase Calderaro’s insightful exegesis of these poems. Instead, I

focus on “The Confession,” where Bliss pursues a similar strategy.

In “The Confession,”

originally titled “The Thief,” the reader is offered a glimpse of the

“inventiveness with words” that Bliss employed in “Transubstantiation” and “Introibo ad Altare Dei.” However, in

“The Confession,” the sonnet form restrains her choice of rhyme, yet frees her

to explore the theme of unrequited love.

In the first four

lines, the speaker provides the context for her seeming act of penitence:

Shall

I confess to you I am a thief,

And

do your gracious absolution ask?

Would

you Confessor, promise me relief

If

I should set myself to this silly task?

The use of the

word “silly” undermines the supposed piety of the confessor and signals the

unrepentant tone of the poem:

How

sweet would perils be, if you but were

My

judge, to weigh the balance of my crimes,

And

to impose a punishment severe,

To

hear your voice I’d sin a thousand times!

Then, at the volta, Bliss introduces the motive for

the “confession”:

Yes,

I will risk your high and dread displeasure,

Last

night I lay beside you in a dream

And

stole your love, and broke into your treasure

Of

hidden wealth; and strangely it did seem

That

your delight nigh equalled mine! I know

I

only dreamt it – do not tell me so!

What intrigues me is

the clever subterfuge of dream that Bliss uses for the speaker’s desire for the

consummation of love: “Last night I lay beside you in a dream/And stole your

love, and broke into your treasure/Of hidden wealth,” and then, in a plea of

recognition asserts, “and strangely it did seem/That your delight nigh equalled

mine! I know/I only dreamt it – do not tell me so!”

According to the

American poet Robert Frost, “Poetry provides the one permissible way of

saying one thing and meaning another.” The tension of paradoxical utterance is

the source of poetic complexity and rewards with repeated readings. Eliot

Bliss’s work embodies this principle and Calderaro is to be congratulated for recovering

these poems from obscurity, and for bringing them back to our attention.

Kindle Edition

About the Author

Michela A.

Calderaro an Associate Editor of Calabash: A Journal of Caribbean Arts

and Letters, teaches English and Postcolonial Literature at the

University of Trieste (Italy). Dr. Calderaro's critical works include a book on

Ford Madox Ford and numerous articles on British, American and Anglophone

Caribbean writers.

1 comment:

Neglected authors fascinate me. While the particulars for their disregard may vary over time and from culture to culture, one thing remains constant: their perseverance despite official recognition. Such is the case of Eliot Bliss, a “white, Creole, and lesbian” Jamaican novelist and poet whose collected poems have been resurrected by Michela A. Calderaro in Spring Evenings in Sterling Street.

Post a Comment